November 2024 | Volume 26 No. 1

When Foreign Governments Meddle in Elections

Listen to this article:

When Professor Dov Levin of the Department of Politics and Public Administration was embarking on his PhD at the University of California, Los Angeles in the early 2010s, he picked up a book from the library that would open a whole new field to him. The book concerned the 1948 Italian election, when the US intervened overtly and covertly to bring the Christian Democrats to power. To his surprise, Professor Levin discovered very little other research had been done on such foreign meddling in elections. That discovery became an opportunity and he is now one of the leaders in this growing field.

His book Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions, won the 2021 Robert L. Jervis and Paul W. Schroeder Best Book Award by the American Political Science Association, and is part of his ongoing research on interventions by the US and Russia, easily the most prolific meddlers in the world.

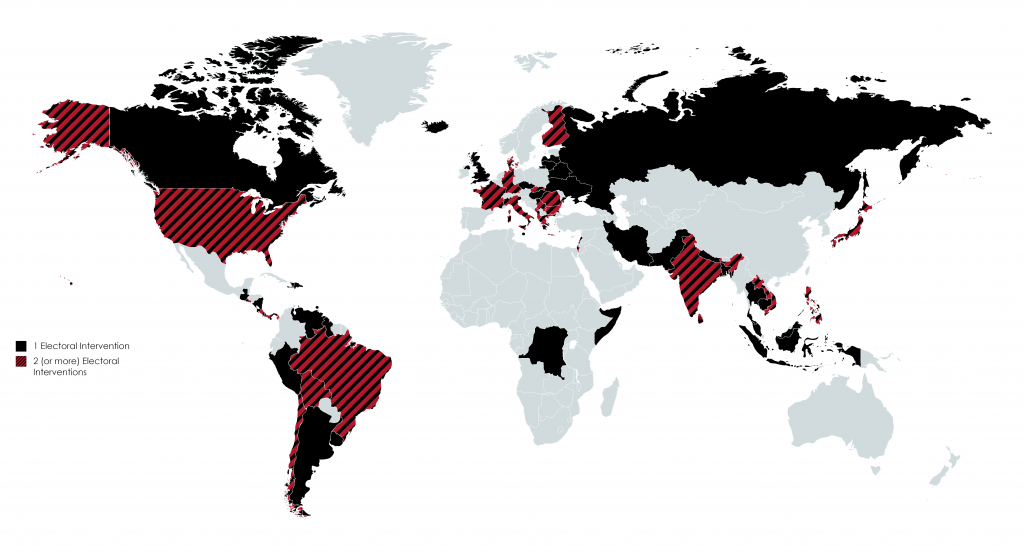

Drawing on multiple sources from the US, Russia and elsewhere, such as archival documents, newspaper articles and the memoirs of former Russian and US spies, Professor Levin has identified more than 180 post-World War II election interventions.

“I was surprised just how common such interventions have been and yet until the last decade, scholars largely ignored them,” he said. “The problem is even somewhat more common now because there are more countries having relatively competitive elections.”

Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions was published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Done because it works

Governments’ interference in elections frequently works, he said. Professor Levin’s research has found the assisted side gets an average three per cent bump over competitors, which is enough in many cases to swing elections.

Perhaps the most infamous modern case was Russia’s intervention in the 2016 US election. It was meant to be secret. Russia spread disinformation about presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and hacked the Democratic National Committee’s website, which turned up damaging information about Clinton. The latter was handed over to Wikileaks anonymously, which then published it on its website. Although the Russian source was later discovered, the desired impact on the US election was achieved.

“Surveys showed that people who checked those documents on Wikileaks were more likely to vote for Donald Trump and an analysis of Google keyword searches found that many people in swing states checked these leaks. The swing was enough to give Trump an electoral college victory,” he said.

That case was unusual because overt, public interference tends to be more successful than the covert, dirty-tricks kind, especially when the covert interference is exposed. Foreign powers may make public statements indicating who they would prefer in power alongside either threats – such as cuts to funding or halts to treaties – or sweeteners, such as the promise of more funding.

Surveys show that the citizens of intervening countries, such as the US, have no problem with electoral interventions by their own government elsewhere, even if their own country has been a target. Yet there are consequences.

A map of US and USSR/Russian partisan electoral interventions between 1946 and 2000.

Consequences for democracy

Electoral interference can increase domestic terrorism, which Professor Levin determined by combining data on interventions and domestic terrorism and controlling for other factors that affect terrorism. He cited the example of Italy in 1976, when the US publicly threatened to kick the country out of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) if the Communist Party won. The favoured Christian Democrats narrowly won, but people lost faith in the system and domestic terrorism increased by more than 50 per cent as a result.

The US also intervened in Russian elections in 1996 to successfully support Boris Yeltsin, an erratic alcoholic who had overseen an economic collapse, against a reformed Communist Party. That ultimately led to the rise of Vladimir Putin. Both countries are also known to have intervened in the 2004 Ukrainian election (the US-backed side won) and in numerous other elections around the world. During the 2019 UK elections, Donald Trump said the UK’s trade agreements with the US would go more smoothly if Boris Johnson was elected.

When such interventions do not lead to domestic terrorism, they can nonetheless weaken democracy. Professor Levin found covert intervention by foreign states could increase corruption in the target country, thereby undermining public support for democracy and increasing support for leaders who do not care about democracy.

And if an intervention fails? Professor Levin found the intervened country usually does not retaliate and will rebuild relations with the intervening power. “Most times, they let bygones be bygones,” he said.

I was surprised just how common such interventions have been and yet until the last decade, scholars largely ignored them.

Professor Dov Levin