November 2020 | Volume 22 No. 1

Sex among the Masses

Erotic literature in traditional Chinese society is famously associated with The Plum in the Golden Vase, or Chin P’ing Mei, which explicitly details the sexual goings-on of a wealthy merchant with multiple wives and concubines. But merchants and scholars did not have a monopoly on erotic or pornographic literature in Imperial China. As Professor Wu Cuncun, Head of the School of Chinese, has discovered, the lower classes were also keen to record passionate and lovelorn events of their lives.

Professor Wu has researched extensively about same-sex love in China under the Ming and Qing dynasties and recently has been exploring the love lives of lower-class women in the late Imperial era as reflected in their songbooks.

Pornography and an appreciation of the lives of commoners started to take hold in China in the late 16th century when the country was in the nascent stages of modernity. Alongside growing urbanisation and individualism, “suddenly many literary works appeared that are quite erotic and more focussed on common people rather than only the upper class. People started to realise that everyone has a life and pleasure is important,” she said.

These works are revealing of their society. In same-sex erotica, Professor Wu found a strong divergence in the motivations of the elites – who viewed homosexuality as a pure form of love unencumbered by social duties such as marrying for connections – and the lower classes. The short-story collection Longyang Yishi tells stories from the perspective of male prostitutes who mostly came from poor families and were preoccupied with money, not love.

“There are stories about how to cheat the clients, how to make more money. There are also stories about how prostitutes got cheated – they are promised big money and then the client escapes just after sex without paying. Money is very important to them to buy clothes, which are their main form of property,” Professor Wu said.

“These men did not have much dignity because even though traditional Chinese society did not consider homosexuality to be a moral sin, they still discriminated against the passive role of the male prostitute.”

‘Bun booth books’

The sexual and gender concerns of the lower classes in Imperial China are not easily uncovered. In addition to homosexuality, Professor Wu has also been investigating the lives of lower-class women as contained in songbooks that are full of the language of the street – as well as abbreviated versions of Chinese characters.

The songbooks are palm-sized and only four to 12 pages long, bound cheaply in glue rather than thread, and printed on the same kind of paper used to wrap buns. They were sold from bun shops, giving them the name ‘bun booth books’ (mantoupu ben).

Professor Wu first learned of them only in 2018 while researching erotic literature at a library in St Petersburg. “It was a big surprise for me because I had never seen books like this before. I discovered that there had been almost no research done on them,” she said.

She has so far tracked down songbooks in libraries in Russia, Japan, Taiwan and Beijing that date from the mid-1800s to the 1930s and contain songs and poems about women’s lives, including adultery, sex before marriage, pregnancy and illegal births. “These are mostly very sad songs about falling in love, not being able to marry, and giving birth. Sometimes they keep the baby, sometimes they kill the baby,” she said.

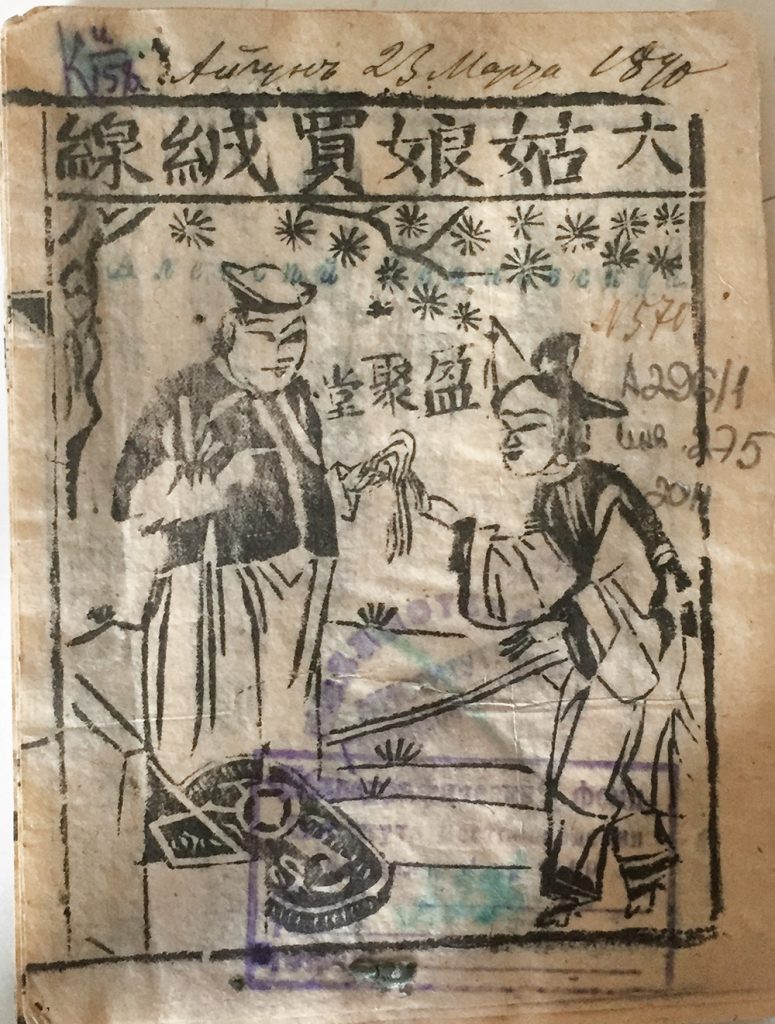

Cover page from the songbook A Girl Went to Buy Woolen Thread.

Miserable but more free

But despite that misery, the songs also reveal that lower-class women had more social space than their upper-class counterparts, who were confined to home.

“In these stories, you can find the woman not only works at home doing the cooking and so on, but she also labours in the field. She helps bring home the bread, so she has a say in the family. Because of this, if the woman has an affair, sometimes the husband can’t do anything about it,” she said.

The joys and sorrows of extramarital affairs are a common theme. In one song, for instance, a woman is visited by her lover then gives him money for a meal and a donkey ride home because she wants him to have comfort, then she cries because they cannot live as man and wife.

Although the songwriters’ names are not included in the bun books, the fact that they take the women’s perspective persuades Professor Wu that these are indeed women’s songs. “These are original voices from lower-class women about their sexuality and social life. They aren’t elite women’s stories or stories retold by men,” she said. She continues her search for bun booth books in collections around the world.

Suddenly many literary works appeared that are quite erotic and more focussed on common people rather than only the upper class. People started to realise that everyone has a life and pleasure is important.

PROFESSOR WU CUNCUN