May 2021 | Volume 22 No. 2

Humans in the Wild

(Courtesy of Moritz Muschick)

Unusually for an ecologist, Dr Hannah Mumby’s first interest was anthropology. She switched track to study the ecology of big mammals beyond primates – especially elephants – to see if it could lead to new questions about our own species. But the more she studied the creatures, the more fascinated she became with them. Until, a decade later, she came full circle and realised humans need to be part of this picture, too.

“Generally, when you study big mammals there is interaction with humans. Rather than trying to erase that impact, I thought the interaction itself could give interesting information,” she said.

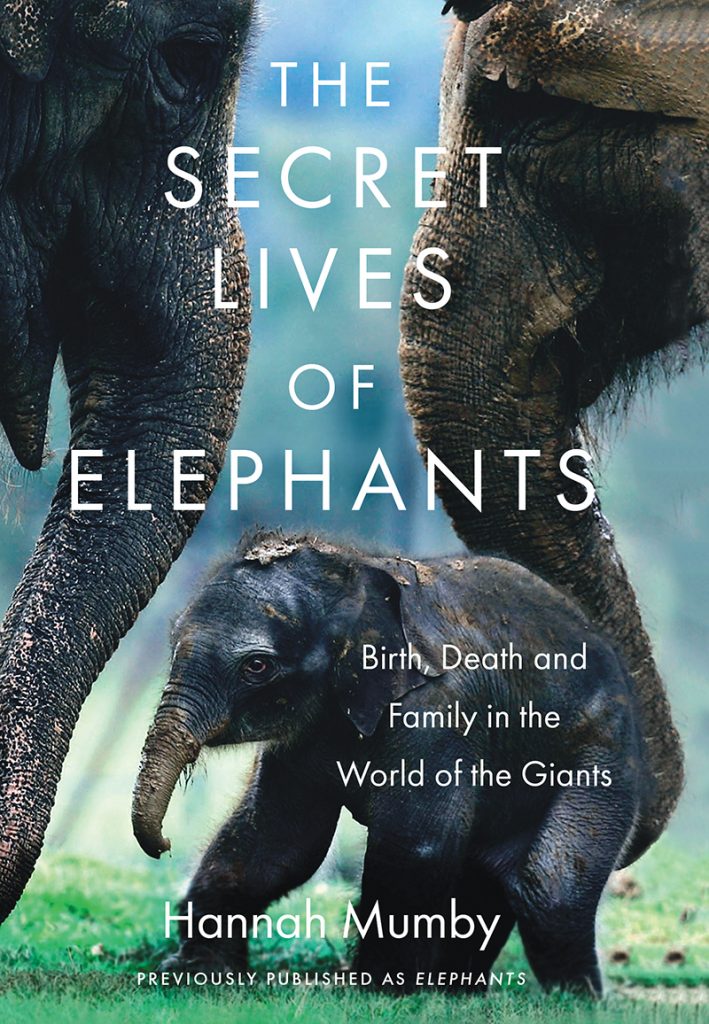

The inspiration for this switch came after writing a book for the general public, called Elephants: Birth, Life and Death in the World of the Giants, that was published last year. It features observations about elephants and stories of her own experiences.

“What you report in academic papers is about one per cent of the actual experience of what it feels like to be there with the animals, how your heart races when you mess up and an elephant charges you or the heartbreak when you see a poached elephant with its tusks removed or feet removed or even its skin. Or when you see a family group playing together in the water.

“After I wrote the book, I wanted to try to open up the research a little bit more and bring in the human dimensions and interactions.”

Mutual effects

That realisation also coincided with Dr Mumby’s arrival in Hong Kong in early 2019 from Cambridge University, just after she finished her draft of the book. She set up the Applied Behavioural Ecology and Conservation Lab that studies animals on the one hand – such as their genetic networks and vocalisations – and human-wildlife interactions on the other.

In Nepal, for instance, she and her team have been studying the relationship between mahouts and their elephants. She wanted to know the mahouts’ thoughts about recent changes to elephant care, such as stopping elephant rides and instead having visitors walk alongside the animals, and rather than chaining, letting them move freely around corrals and interact with each other.

“The responses from the mahouts to this were very nuanced. They liked that elephants could move around. However, they were also concerned about the elephants spending a lot more time with other elephants because that meant they might not listen to the mahout as much and maybe there would be a risk to safety if the elephant isn’t as responsive,” she said.

Apart from elephants, Dr Mumby’s team are looking at Hong Kong’s wild boar population, for which there are increasing anecdotal reports of sightings and interactions with humans. Part of the research is analysing media reports to find who is speaking, in what language, and what they say, among other factors. Another study is investigating the impact on boars’ diet and behaviour when people leave out food for them. The team have also just started studying human-buffalo interactions on Lantau Island.

Interviewing mahouts in Nepal.

(Courtesy of Matthias Egeler)

Dr Mumby’s team have also started studying human-buffalo interactions on Lantau Island.

Conservation ‘a necessity’

But her greatest passion remains the elephant and how to protect this vulnerable animal. “Some of my experiences have been beautifully exciting, like having a baby elephant named after me in Myanmar. Some have been just tragic – elephants hit by trains, the poaching crisis, and the impact that has on researchers and rangers. In my book I’m trying to say, what do we do next? What could we be funding more? Is there hope?”

There are already a lot of organisations and researchers on the ground tracking and trying to protect the elephant and she would like to see more stable, long-term support for them. “One of my biggest concerns about conservation is that we’ve made it a luxury. People do it from philanthropy rather than as a necessity, and it can seem like whim as to what gets funded. But it shouldn’t just be charity. It’s essential to our future because it’s essential to the functioning of ecosystems.”

Dr Mumby also recognises the flip side to this: conservationists tend to demonise people as the problem. “Every conservation textbook I read is essentially about how everything was perfect until humans messed it up. As an academic community, we’ve internalised this narrative. We have to frame people as the solution as well. Of course, people are going to do things that damage the environment in order to live, but we still have to see them as the solution.

“I don’t have any illusions that I can make miracles happen, but I still have a bit of wild hope,” she added.

Elephants: Birth, Life and Death in the World of the Giants was released by HarperCollins in May 2020. A paperback version titled The Secret Lives of Elephants was out this spring.

The Secret Lives of Elephants: Birth, Death and Family in the World of the Giants

Author: Hannah Mumby

Publisher: HarperCollins

Year of Publication: 2021

Every conservation textbook I read is essentially about how everything was perfect until humans messed it up. As an academic community, we’ve internalised this narrative. We have to frame people as the solution as well.

DR HANNAH MUMBY