November 2019 | Volume 21 No. 1

Cover Story

Two Takes on China’s Migrant Workers

Migrant workers have long had a poor image in China. When they started to flood into cities in the 1980s and 1990s to fill factory jobs, they were regarded by both urban residents and official state media as uncivil, disorderly and crime-prone and they were denied hukou permits that allow access to services and housing. This negativity provoked rising labour unrest and other problems of governance of a population that numbered at least 200 million, which led to a softer approach from the government.

This century, the government has romanticised migrant workers in the popular media and provided them with cultural recognition through two state-sponsored rural migrant museums that opened in Shenzhen in 2008 and Guangzhou in 2010.

Dr Qian Junxi, Assistant Professor of Geography, and his collaborator Dr Eric Florence of the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China have been studying the contents of these museums, as well as another founded by migrants. Their findings suggest the state still has a long way to go in depicting the life of migrant workers as they experience it.

“At the centre of the state representation is an East Asian Confucian meritocracy where if you contribute to society’s development and to the economic prosperity of our country, then you have earned our respect. This respect is not because you are a citizen, but because you have proven yourself to be economically useful,” Dr Qian said.

State’s preferred models

The state museums offer two overlapping and interrelated models of migrant workers. One model is docile and industrious and willing to sacrifice himself or herself for the country’s economic development by working for relatively low economic returns.

“This is a glorified image of rural migrant labourers and it does not recognise that their labour should be properly rewarded. Because by talking about a noble cause, you don’t need to be concerned about rights and economic returns,” he said.

The other model is the self-driven, entrepreneurial worker who achieves economic success. “This type of worker represents the neoliberal mentality that you take responsibility for your own economic well-being and improvement – there is no collective responsibility of the public sector. But only a very small proportion of rural migrants achieve this success. The vast majority suffer from institutional discrimination and inadequate access to resources and opportunities and protection of rights. So it is very difficult for migrants to follow the template of those successful figures,” Dr Qian said.

The state migrant museums also emphasise the state’s generosity and care towards workers. Various levels of government have given them growing access to services and labour protection, and the living conditions in migrant villages have improved. “However, all these piecemeal modifications tend to obfuscate the fact that the hukou system remains, which is the primary source of rural migrants’ marginality,” he said. As a result, strikes, protests and collective resistance persist, as well as a failure by institutions to protect workers’ rights and welfare.

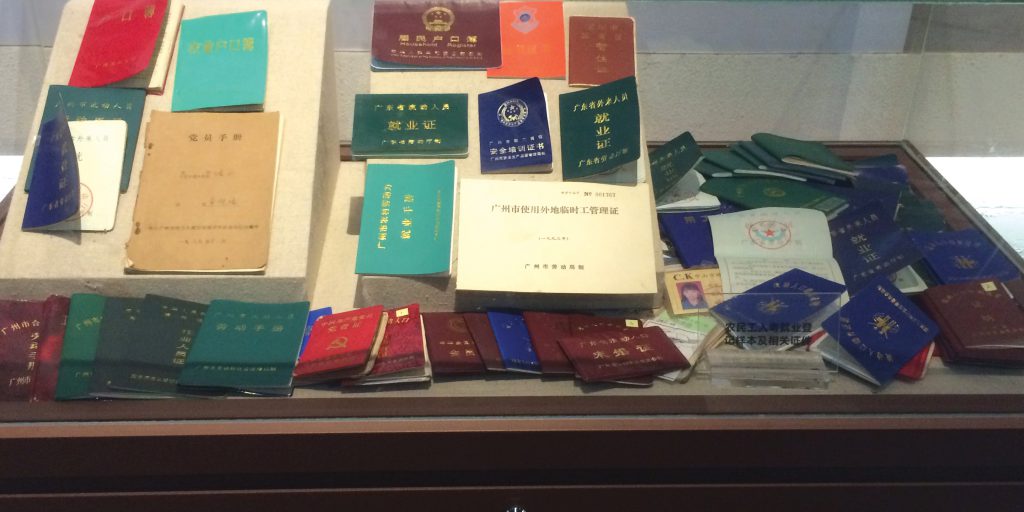

Display of permits and certificates needed for working in the city.

Replica of a workshop, but now deprived of labour activities and relations.

Workers’ perspective

These issues are not mentioned in the state museums, but they do have a forum in the worker-led Culture and Arts Museum of Migrant Labours that is tucked away in a temporary structure near Beijing’s main airport. Its displays offer a rebuke to state-sponsored narratives.

For example, while state museums portray residence permit cards as gateways to the future for rural migrants, the Beijing museum presents them as a burden because of the huge effort required to obtain the necessary documentation to qualify for these cards.

The Beijing museum also shows how workers are exploited and oppressed, such as the strict restrictions placed on workers’ time and socialising at Foxconn factories, and how employers refuse to provide adequate protection or even medical assistance for labour-related injuries.

“The government tends to portray labour as a way for migrants to achieve mobility, but the migrants have feelings of alienation and of being separated from their support network. They feel subjected to the exploitative mechanisms of a capitalistic economy,” he said.

Dr Qian and another collaborator, Quan Gao of Newcastle University, UK, have begun looking at how workers cope with this alienation. In Shenzhen, they discovered many migrants attend Christian churches – of nine churches visited by the scholars, more than 80 per cent of the congregations were migrant workers.

“They join for two reasons. One is superficial – they find community there and a social support network. A deeper reason is that they borrow from Christian theologies to make sense of their current situation. They tend to think they are not exploited by capitalism and that their suffering is because they are labouring for God, so they want to better themselves to be better behaved, not quarrel too much and obey the rules,” he said. “We expected these churches to be spaces of resistance, but in fact they turn out to be spaces of co-optation.”

The government tends to portray labour as a way for migrants to achieve mobility, but the migrants have feelings of alienation and of being separated from their support network.

DR QIAN JUNXI