May 2024 | Volume 25 No. 2

A Guide to Tourism in Hong Kong

Listen to this article:

Hong Kong as a travel destination has been many things to many people over the decades. For Western visitors in the 1930s, it was a beach and recreation stop on a round-the-world voyage by sea. After the Second World War, its ‘oriental-ness’ and Chinese culture attracted jet-setters. In the 1970s and 1980s, it became a shopping mecca, especially with visitors from Asia who benefitted from the growing wealth in the region. This century, tourism has been dominated by Mainland Chinese visitors, whose interest has shifted from shopping for luxury goods to exploring cultural and historical sites and places of natural beauty.

Why has it had such a changeable image? Professor John Carroll and research assistant Jodie Cheng of the Department of History have each been investigating the tourism trends, both independently and collaboratively, and how these provide insights into larger societal and political developments.

“Promoting Hong Kong tourism has been an unpredictable and even contentious matter,” Professor Carroll said. “In recent years, as the government has taken a more assertive role in promoting tourism, local residents have also become increasingly concerned about tourism. Meanwhile, visitors have sometimes found themselves entangled in the resulting protests.”

The beginnings of tourism stretch back to the 19th century, when the city was promoted by private shipping firms, travel guide publishers and hotels. In the 1920s, the government itself started to see tourism as a potential revenue source, according to Ms Cheng, who specialises in pre-war tourism in Hong Kong. This led to the establishment of the Hong Kong Travel Association (HKTA) in 1935.

Bustling but sleepy

The narrative at the time was of Hong Kong as the ‘Riviera of the Orient’, featuring beaches, scenery and leisure, albeit with an embedded message. An iconic poster by the HKTA featured colonial buildings against the backdrop of Victoria Peak. “Historians of tourism read that as colonial governments wanting to showcase the facilities they have built and the progress they have made in the colony,” Ms Cheng said. “A picture focussed only on the natural features cannot show this.”

The Second World War halted tourism, but afterwards things took a very different turn. Air travel meant people could make shorter visits, while the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the closing of borders meant Hong Kong became one of the few places where people could experience Chinese culture and gaze at Mainland China. For the government and other actors, including airlines, hotels and travel agents, as well as the new Hong Kong Tourist Association formed in 1957 to pick up where the pre-war HKTA left off, this was a time of opportunity.

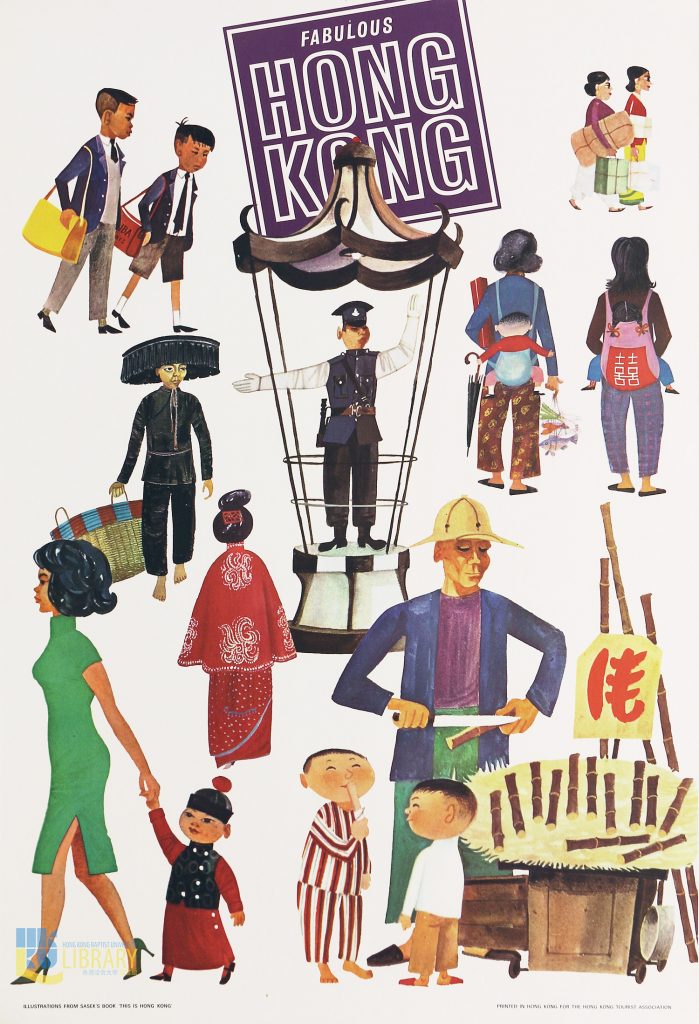

“From the 1950s up to 1997, a range of state and non-state actors tried to promote Hong Kong as a unique place that was culturally Chinese but a British colony and which blended East and West. And from the early 1970s it was portrayed as a bustling metropolis coexisting with the sleepy rural New Territories,” said Professor Carroll, whose research has focussed on post-war tourism.

Fabulous Hong Kong, poster of Hong Kong Tourist Association, circa 1966, painted by Miroslav Šašek. (Courtesy of Hong Kong Baptist University Library Art Collections)

Window on Hong Kong

Tourism also became a window through which Hong Kong people came to think about their city and themselves. “Especially within the contexts of the Cold War and the disintegration of the British Empire, tourism was about more than economics and the movement of people. It became a way for Hong Kong to position itself within Asia and across the globe,” he said.

Interestingly, from the mid-1980s to 1997, tourism authorities struggled to define Hong Kong. The opening of Mainland China meant visitors did not need to come here to experience Chinese culture, so shopping took centre stage, especially for tourists from around the region.

After the handover, things took another turn as the government began to see tourism as a way to brand the city to the world following uncertainty about its future. The Hong Kong Tourism Board was established in 2001 with full government funding and the Culture, Sports and Tourism Bureau was established in 2022.

The biggest change, though, was in the tourists themselves. Following the Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Agreement signed in 2003 (in the wake of SARS), more Mainland tourists poured into Hong Kong.

This has had local impact, including sometimes negative reactions from local residents. But for Ms Cheng, it also reinforces the idea that mass tourism is not just a Western concept. In fact, tourism and travelling are deeply embedded in Chinese history and culture.

“Tourism is almost necessarily a global phenomenon, but by studying Hong Kong, we want to decentralise the narrative from a Eurocentric one of how modern tourism has developed. Asian regions have their own unique travel culture as well. It’s not just a matter of mass tourism spreading here from Europe,” she said.

Tourism is almost necessarily a global phenomenon, but by studying Hong Kong, we want to decentralise the narrative from a Eurocentric one of how modern tourism has developed.

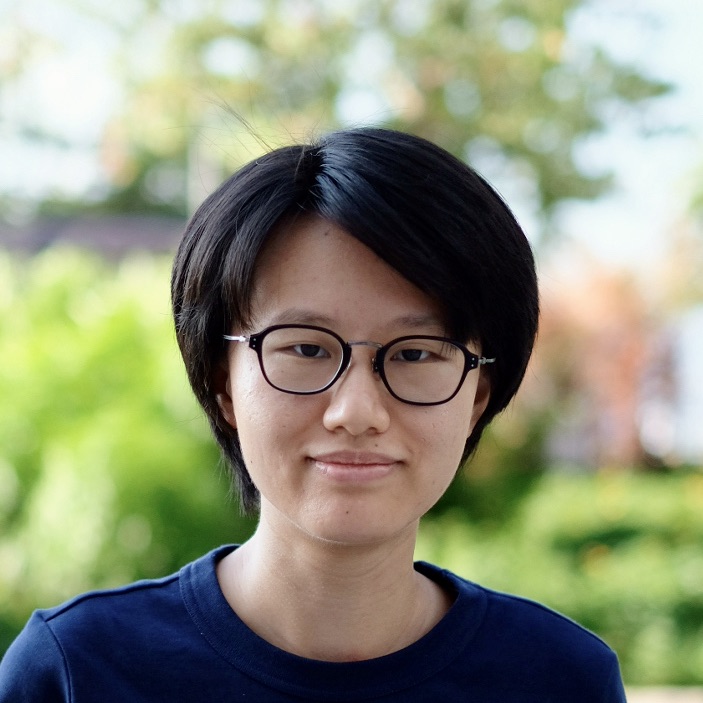

Ms Jodie Cheng