November 2019 | Volume 21 No. 1

Catholics in China: A Survival Story

The history books tell us the facts about the arrival and activities of Western missionaries in China. But what did this mean to the ordinary peasants and missionaries at the time? For Dr Li Ji of the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences and the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, these ‘no-name people’ are her raison d’être. She has spent the past 15 years digging through archives, tracking obscure names and contacts, and letting serendipity take its course.

Her work started in 2004 with a trip to the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris to search its archives. Unlike the Jesuits, who focussed on the elites, the Society recruited missionaries from peasant families in Europe and sent them to live for decades among their counterparts in China. One such family was the Du family of Manchuria, whose three daughters learned to read and write from the church and wrote a series of letters in 1871 to their priest. Dr Li used the letters in her first book, God’s Little Daughters: Catholic Women in Nineteenth-Century Manchuria, published in 2015, to show how Catholicism was disseminated by the priests and interpreted by believers to articulate an awareness of self.

But her fascination with the letters did not stop there. The Du sisters came from Santaizi, which is part of Liaoning province, and Dr Li visited the town where she chanced to meet the descendants of the sisters. Her current research is based around those encounters.

“To my surprise, the whole family is still Roman Catholic. In their home, you can still find icons and pictures of the Virgin Mary. I became very curious to understand how this religious culture survived until today,” she said.

Offering stability

A key factor has been their self-identity as Catholics, which began before they even came to Santaizi. The ancestors of the Du family and others in the area only arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries, having fled conflict and hardship in such places as Shandong, where they had originally converted to Catholicism. In Santaizi, they held onto their faith – not only for benefits such as education, but stability in an increasingly unstable country. Dr Li’s research showed this was a common pattern among Catholic communities in northeast China.

“The missionaries not only built churches and introduced rituals, they instilled ideas of local governance. Because in these border areas where they worked, there were sometimes no local officials or magistrates to take care of the people,” she said.

Dr Li also uncovered evidence of the close relationship between missionaries and Santaizi residents through the writings of French missionary, Alfred Marie Caubrière. He recorded daily conversations, such as elders discussing childcare and quarrels between husbands and wives, using a French romanisation of the local dialect, presumably to help others learn the local language. “These topics showed that he had an intimate relationship with the villagers,” she said.

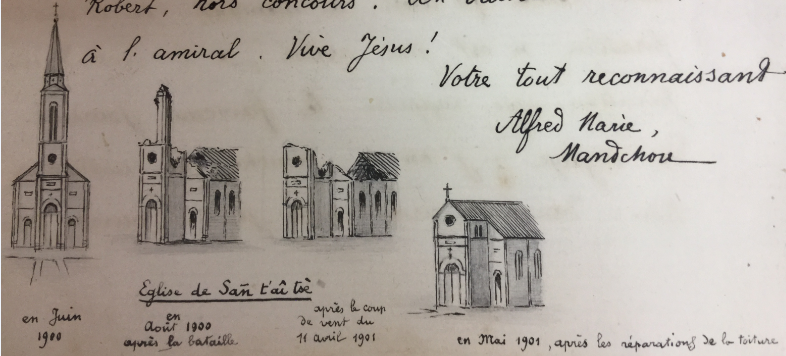

Caubrière also wrote 233 letters to his family in France from 1900 to 1927 recounting village life, such as the story that the Virgin Mary protected villagers during the Boxer Uprising in the early 1900s and a drawing of a girl whose father had just died and who wanted to know what France was like. “Although these are trivial daily life details, they can tell scholars about big issues, like how Western culture or religion changed ordinary Chinese people’s vision of the world,” she said.

The village church before and after the Boxers’ attack in 1900.

Family tradition

However, the Catholic legacy became more complicated when the Communist Party took over and began to rebuild the state. A daughter of the Du family who had joined a convent fled Manchuria to Taiwan with other church members in 1948. A son who joined the priesthood was killed during the Cultural Revolution. The church, which earlier was destroyed by the Boxers and rebuilt, was destroyed again during the Cultural Revolution.

During the more tolerant 1980s, the state allowed the church to be rebuilt again, albeit in a plain style. Still, people remain guarded about revealing their faith because it can cost them job promotions or Communist Party membership. Dr Li found this was not enough to stamp out that faith, though. “Not everyone in the Du family knows the Catholic doctrine, but most think of it as their family tradition. They want to hold onto it because it was important to their ancestors and it is part of their identity.”

Because of that, Catholics are still seen as a threat to state governance, even though they are largely rural, less educated and small in number. “A problem from the state perspective is, how have they survived all these anti-Christian campaigns and movements? They are not fighters, but they have held tightly to their identity. This is not only explained by faith but by their collective memory – of churches being destroyed, of their people being attacked,” she said. “It has strengthened their identity and feeling of belonging.”

Her second book, for which she is now completing her manuscript, will tell their story.

Dr Li’s first book God’s Little Daughters: Catholic Women in Nineteenth-Century Manchuria was published in 2015.

A problem from the state perspective is, how have they survived all these anti-Christian campaigns and movements? They are not fighters, but they have held tightly to their identity.

DR LI JI