May 2020 | Volume 21 No. 2

Gut Reaction

Exercise is generally recognised as highly beneficial for your health, but it works better on some people than others. New research suggests that people possessing certain gut microbes may in fact gain better metabolic outcomes from exercise than others.

“The prevalence of diabetes (particularly type 2 diabetes) has been reaching epidemic proportions globally,” said Professor Xu Aimin, Chair Professor of Metabolic Medicine in the Department of Medicine. “Although there is no cure for diabetes, it can be prevented by early lifestyle interventions, with exercise being the most cost-effective strategy. However, until now, the molecular transducers mediating the metabolic benefits of exercise have remained largely unclear.”

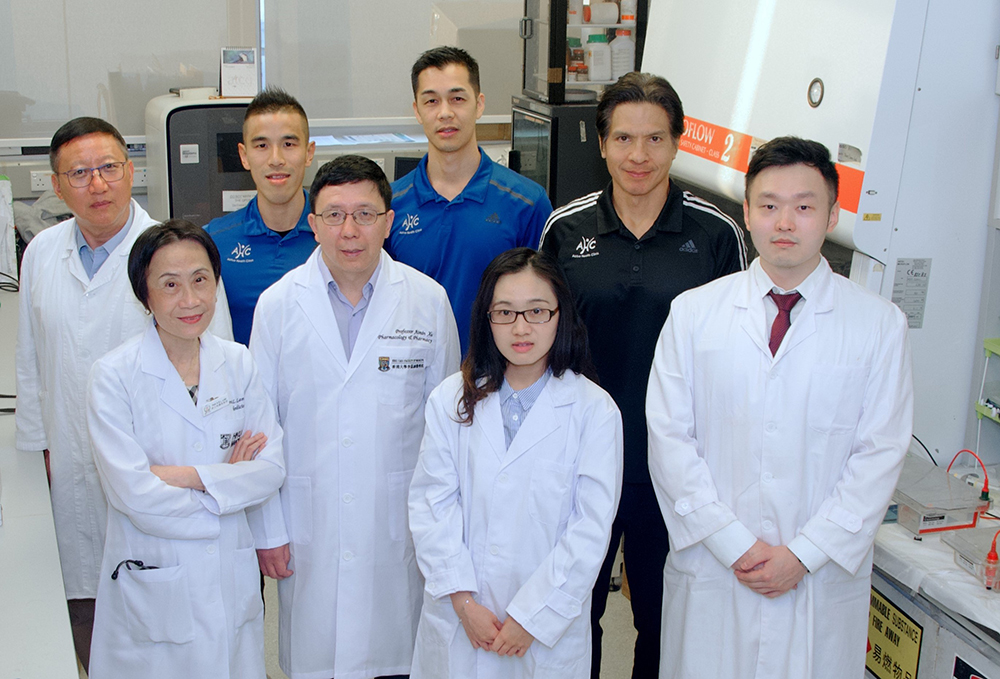

To address this issue, his team – including co-corresponding authors Dr Michael Tse, Director of HKU’s Centre for Sports and Exercise, and Dr Gianni Panagiotou, Head of Systems Biology and Bioinformatics, Hans Knoell Institute – decided to identify exercise-responsive factors comprehensively using an unbiased multiomics approach.

Asked why they concentrated on the gut, Professor Xu said: “Our gut harbours a complex community of over 100 trillion microbial cells which influence human metabolism, nutrition and immune function, while disruption to the gut microbiota has been linked with obesity and diabetes. Therefore, we wanted to investigate whether exercise mediates the metabolic benefits by reshaping gut microbiota, and for those people who do not respond well to exercise, whether their ‘exercise resistance’ is due to maladaptation of gut microbiota.”

The research team conducted a 12-week randomised controlled trial (RCT) in the form of a high-intensity exercise training intervention on 39 Chinese men with pre-diabetes. The participants, who had never taken medication for their condition, were randomly assigned to either a sedentary control group, or to a group that underwent the supervised exercise training. All participants were instructed to maintain their usual diet.

The results showed that while all the participants exhibited a similar degree of weight and fat mass reduction, only 70 per cent of them showed significant improvements in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, whereas the remaining 30 per cent were not responsive to exercise.

“Analysis revealed obvious differences in exercise-induced compositional and functional alterations in gut microbiota and its metabolites between responders and non-responders,” said Professor Xu. “The microbiome of responders exhibited enhanced capacity for biosynthesis of short-chain fatty acids and catabolism of branched-chain amino acids, whereas that of non-responders was characterised by increased production of metabolically-detrimental compounds.

“The results suggest that gut microbiota and its metabolites serve as important contributors to the metabolic benefits of exercise intervention. They also identify maladaptation of gut microbiota as being responsible for those individuals who do not respond to exercise.”

Professor Xu Aimin (second from left, front row) and his research team, including Professor Karen Lam Siu-ling (first from left, front row) and Dr Michael Tse (first from right, second row).

Volunteers participating in a 12-week supervised exercise training intervention.

Maximising the benefits

This is one of the first interventional RCT studies providing clear evidence of the role of gut microbiota on metabolic health. The findings raise the possibility of maximising the benefits of exercise by targeting gut microbiota; and also offer new insight for clinicians and exercise specialists to target the microbiome of exercise non-responders as another means of better enhancing therapeutic interventions.

While acknowledging that this discovery has big implications for diabetes sufferers, Professor Xu emphasised that despite the existence of exercise resistance, physical exercise remains the most cost-effective strategy for the prevention and treatment of diabetes. “We observed a quick improvement in insulin sensitivity within only four-week period after commencing the high-intensity training, in the absence of any dietary changes. This finding suggests that glucose metabolism can be improved in a portion of individuals with pre-diabetes by even short-term modifications to their exercise habits.

“For non-responders, exercise alone may not be enough but this doesn’t mean exercise is useless. For these subjects, more intensive interventions, a combination of exercise training and targeted dietary intervention to modulate gut microbiota, are required to achieve a better therapeutic effect,” he said.

In addition, the team is looking at the implications for improving the efficacy of exercise for people not suffering from diabetes. “We tried to establish a model from our study, which could first predict the probability of whether an individual could benefit from exercise,” Professor Xu said. “If they did not show to benefit from exercise, we could further analyse the unique metabolic characteristics of the gut microbiota and use probiotics, prebiotics or targeted dietary intervention to fine-tune the gut microbiota, thus restoring responsiveness to the metabolic benefits of exercise training.

“Interventions could be modified based on our prediction model to classify if one is a responder or a non-responder. By doing so, we are seeking the possibility of people taking some types of supplements to enhance the microbiome to make the gut more responsive to exercise. It also helps exercise practitioners ‘prescribe’ exercise plans and strategies based on an individual’s responsiveness.”

The results suggest that gut microbiota and its metabolites serve as important contributors to the metabolic benefits of exercise intervention.

PROFESSOR XU AIMIN