May 2022 | Volume 23 No. 2

Something to Chew on

Patients with asymmetrical jaws, where the left and right sides are of unequal lengths due to differing growth rates or trauma, have a lot to deal with. They have functional problems with eating and speaking and low self-esteem due to the impact on their appearance. Dr Mike Leung Yiu-yan, Clinical Associate Professor of Dentistry who runs the largest centre in Hong Kong for orthognathic, or jaw correction, surgery, noticed something else: they can also be in pain.

In a study involving 134 patients with jaw joint pain, or TMD (for temporomandibular disorder), he compared patients with and without facial asymmetry. TMD was significantly more prevalent among those with asymmetry.

“In the normal population, some studies have shown less than 10 per cent of the population is affected by jaw pain. But with asymmetry, we found two-thirds were affected. This makes me think that the asymmetry is causing the pain because of imbalances in the musculature due to the bite force,” he said.

“The next step was to see whether orthognathic surgery that corrects the asymmetry could lead to an improvement in pain.”

Dr Leung and his team drew on their experience with 3D modelling and 3D printing to come up with a solution that not only reduces pain in patients with asymmetry, but also provides more reliably accurate jaw correction.

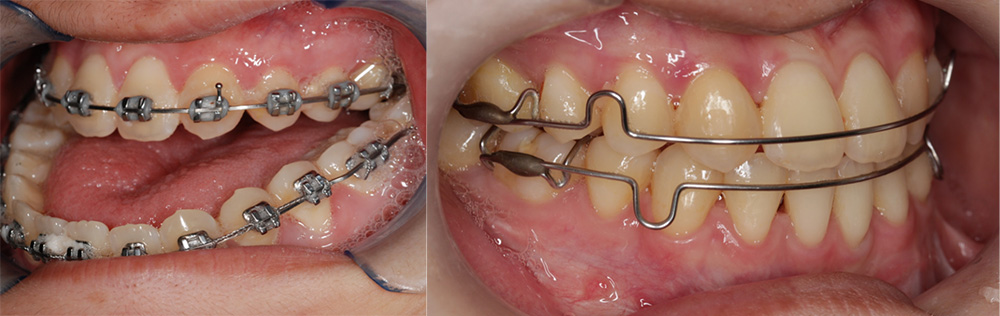

(Left) Photo of a patient with an asymmetric face and a severe reversed bite, that affected her eating function and caused jaw joint pain. (Right) Photo of the same patient after surgery to correct the large reverse bite.

A 3D view

The traditional approach to jaw surgery involves using stone models of a patient’s jaw, manipulating the model into the correct position and creating an acrylic wafer of that to guide surgeons. The surgeons then cut the jawbone accordingly, move it into place and fix it with titanium plates. But the outcome can be subject to errors.

“It’s a bit tricky,” he said. “There may be errors when we transfer the model to the surgery, or errors in the lab work or in the measurements. And some people have faces so asymmetrical to start with that we only see the teeth and may not appreciate the whole problem.”

Instead, Dr Leung and his team worked with a CT scan, which gives a three-dimensional view, to simulate movement and design the titanium plates. With the help of an industry collaborator, the scan results were turned into 3D-printed plates that are to the exact specifications of the patient’s anatomy, which negates the need for the guiding wafer. Although some private companies do both 3D scans and printing, the surgeons in this case have better control over the whole process and obtain the titanium plates in a shorter timeframe (private firms can take a few months).

“We’ve analysed the results of our approach and it’s proved to be very accurate,” he said. “With open-source programs, this will one day be a very popular approach and it will also reduce the cost and offer safer treatment.”

Regaining normal function

Most importantly, it reduces jaw pain. In a follow-up study, the prevalence of TMD in patients with facial asymmetry fell by 58.3 per cent six months after surgery. Patients typically leave hospital within two days and their jawbone heals within six weeks.

“The surgical correction of facial asymmetry allows a normalised chewing function and a corrected bite, and now we prove it also helps in treating TMD. Many people misunderstand that orthognathic surgery is for aesthetic reasons. In fact, the correction is to improve the sufferer’s function as well as reduce pain symptoms,” Dr Leung said.

Most of his patients are in their teens or 20s (some are older, mainly those who suffer from obstructive sleep apnoea due to a short jaw), and the impact on them goes well beyond physical symptoms.

“The patients start to feel so much more confident afterwards. They start to put on make-up, they stand up straight walking into my clinic, they speak to me totally differently,” he said, and their parents often remark that their child looks as they did when they were 12 years old – before growth spurts deformed their jaw.

“I tell my trainees that what is important is to always try to meet the expectations of patients, and I tell patients honestly what I can and can’t do so they do not have false hope. No one has perfect symmetry and some people’s faces are like a banana – no matter how you cut it, you can’t find a mirror image. But we can make it more symmetrical than it was,” he said.

The patients start to feel so much more confident afterwards. They start to put on make-up, they stand up straight walking into my clinic, they speak to me totally differently.

DR MIKE LEUNG YIU-YAN