May 2021 | Volume 22 No. 2

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman

(Courtesy of the University Archives of HKU)

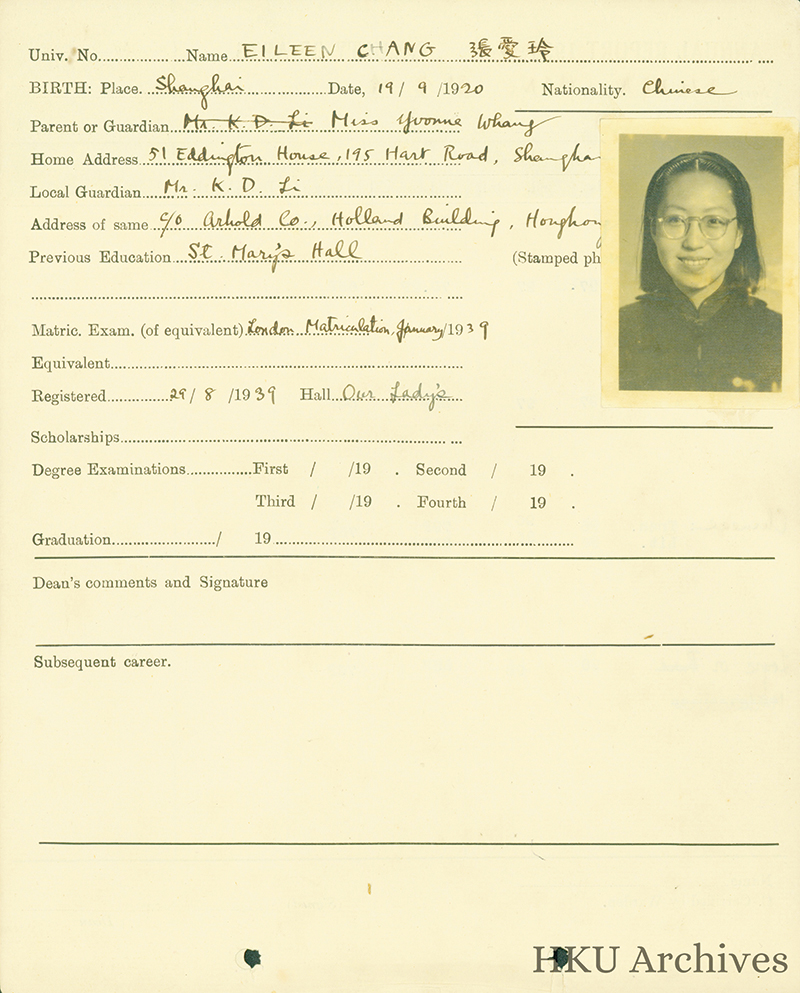

Eileen Chang (1920–1995) began her writing career in the early 1940s in the Japanese-occupied city of Shanghai and went on to become the most prominent author and public intellectual in the besieged city. Educated bilingually from an early age, she enrolled at HKU in 1939, only to see her college education brought to an abrupt end in 1941 by the bloody Battle of Hong Kong. She left the war-torn city and returned to the equally ravaged metropolis of Shanghai, an experience that would find recurrent expression in both her fiction and essays. Her literary works that depict a Hong Kong life include ‘Love in a Fallen City’, ‘Jasmine Tea’ and ‘From the Ashes’.

As one of China’s most influential writers, Chang has of course been the subject of other exhibitions, but there is plenty that is new in this centennial celebration – Eileen Chang at the University of Hong Kong: Historic Images and Documents from the Archives. Professor Nicole Huang, Chairperson of the Department of Comparative Literature in the Faculty of Arts and a renowned ‘lifelong’ Chang scholar, curated this centennial celebration in collaboration with the University Museum and Art Gallery (UMAG), and described her excitement at these new discoveries.

“The HKU archives proved both rich and fruitful, the archivists did a wonderful job,” she said. “As a Chang scholar, I felt almost as though this stuff was just waiting for me to find it, as if it were my destiny! What we found includes more information about her time at the University, and also discoveries that cleared up some misunderstandings.

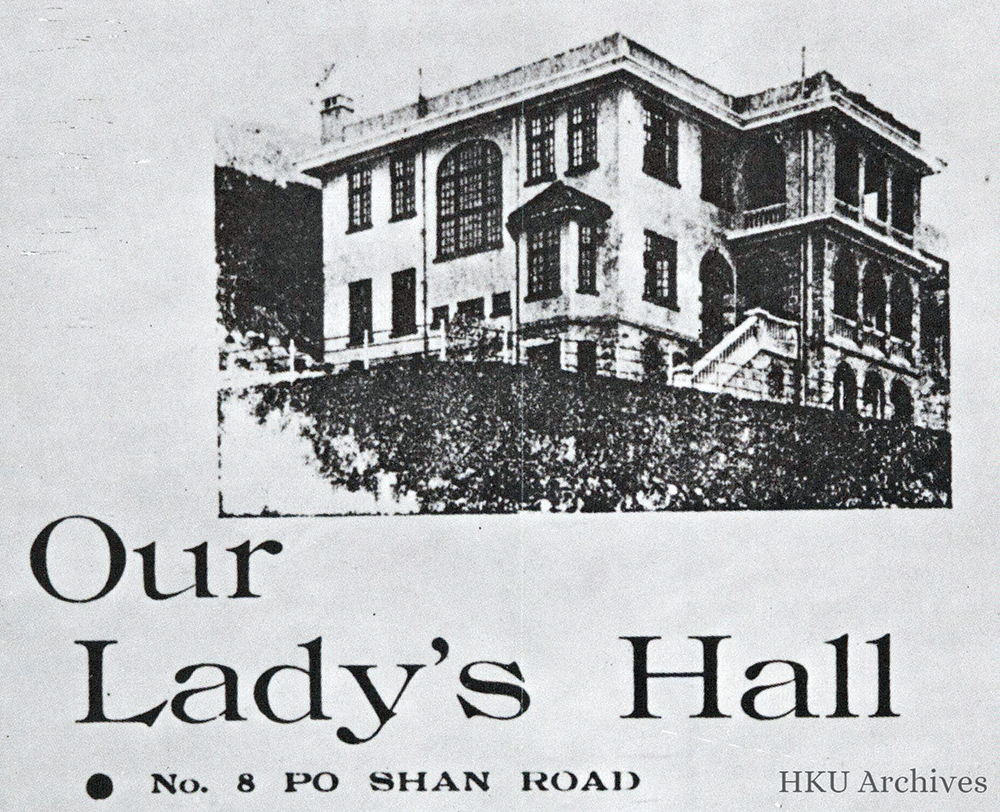

“Previously, we knew she was here and that the war prevented her from graduating, but in the past we had insufficient information about her daily life,” she continued. “We found clear evidence that she lived off campus in Our Lady’s Hall, a large house located up the hill on Po Shan Road, which was the first HKU women’s hostel and was run by nuns of the French Convent School. Now we have a clear picture of where she lived, we can even picture her daily trips up and down the path that connected campus and Our Lady’s Hall. To numerous Chang readers, this clarification is much appreciated.”

Eileen Chang’s HKU student registration and transcript.

(Courtesy of the University Archives of HKU)

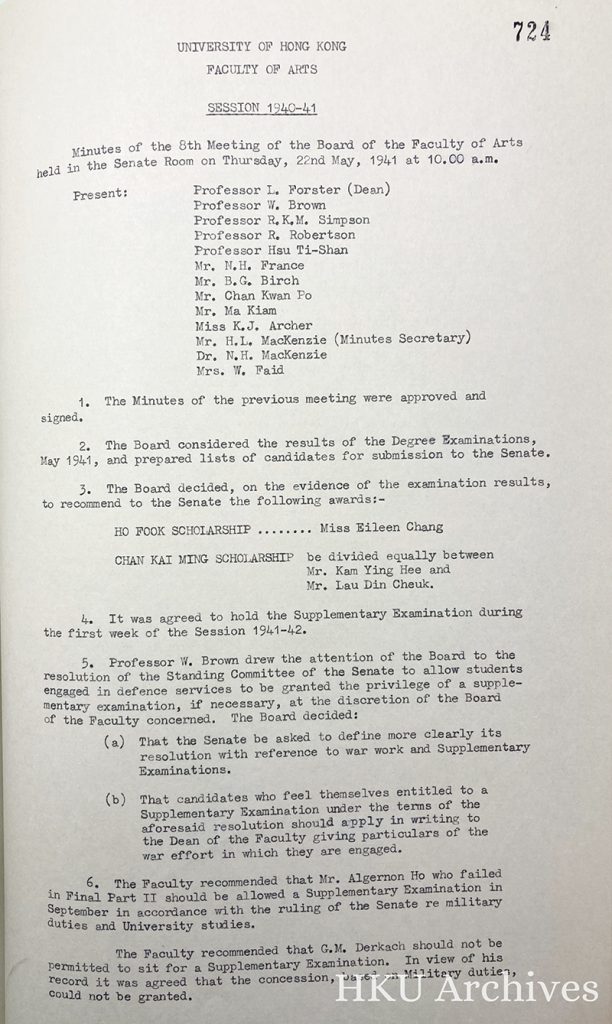

Minutes of the Arts Faculty Board meeting, report on Eileen Chang selected to win a Ho Fook scholarship, May 22, 1941.

(Courtesy of the University Archives of HKU)

Charismatic teachers

The archives also revealed more about the kind of liberal education she received at HKU, and the factors that contributed to her becoming a writer. “In 1942, she became a literary sensation, and the narrative has always been that this happened overnight,” said Professor Huang. “But her education at HKU played a huge role in her success: she took classes with the charismatic history teacher Norman France, and she took Chinese literature and history classes with Professor Hsu Ti-shan, a towering intellectual figure in pre-war Hong Kong.”

France would be killed during the war, but he appears in fictional form in Chang’s essay ‘From the Ashes’ and her novels Little Reunions and The Book of Change. It is widely believed that the Chinese literary professor in Chang’s short story ‘Jasmine Tea’ was modelled after Professor Hsu.

“Before we knew little about her studies, but now we find it all traces back,” said Professor Huang. “France and Hsu were both top-class teachers and they played a major role in developing her intellectual powers, shaping her views of history and influencing her style of writing.”

References to HKU and her friends, teachers and associates here liberally inhabit Chang’s books. There’s even a description of the Fung Ping Shan Library – which, nearly 80 years on, is housing this exhibition in her honour – where, surrounded by books, she felt like ‘a child in a cake shop’ (The Book of Change).

Our Lady’s Hall.

(Courtesy of the University Archives of HKU)

The face of war

Undoubtedly too, Chang was at HKU at an important time in its development. “The 1930s saw a major reform in how liberal arts were taught at the University – a liberalisation of the arts education,” said Professor Huang. “During the early years of HKU, there were few women. Beginning from the early 1930s, more women enrolled every year and by the late 1930s, female students in the Faculty of Arts even outnumbered male students. Gender dynamics on campus were changing, and Chang had come from a background of war brewing in China. It was a meaningful moment in the University’s history, and all of this would play a part in how and what she wrote. She was at HKU when the Japanese invaded. She stared into the face of war, and writing-wise this was pivotal. She decided to write and to write with a great sense of urgency. The overnight literary sensation in Shanghai grew directly out of her years in Hong Kong.”

The narrative that emerges from the exhibition and the new archival discoveries explains why HKU was important to Chang and why the writer would become important to HKU. “It is a two-way relationship,” said Professor Huang. “It defines the University’s role as guardian of Chang’s literary heritage, and it also marks her as a unique window from which we illuminate an important chapter in the history of this great institution.”

Visit the virtual exhibition here.

She was at HKU when the Japanese invaded. She stared into the face of war, and writing-wise this was pivotal. She decided to write and to write with a great sense of urgency. The overnight literary sensation in Shanghai grew directly out of her years in Hong Kong.

PROFESSOR NICOLE HUANG