May 2021 | Volume 22 No. 2

Children of the Quake

After Tōhoku was rocked by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami in 2011, many commentators were struck by the absence of violence, looting and chaos, which they attributed to the innate calmness of the Japanese character. To Dr Janet Borland, Assistant Professor of Japanese Studies, that assertion was a call to arms.

Having lived through the Kobe earthquake in 1995 and as an historian of Japan, she decided to set the record straight with Earthquake Children: Building Resilience from the Ruins of Tokyo. Her book, which won the 2020 Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities First Book Prize, chronicles the difficult path the country has hewn in coping with natural disasters.

The catalyst for Japan’s transformation was the Great Kantō Earthquake, which struck Tokyo on September 1, 1923. It resulted in the deaths of more than 100,000 people and led to fundamental changes in a society that, despite a history of major earthquakes, was wholly unprepared. There had never been drills or practice responses, and most buildings were built of wood.

“Fires burned for three days, rumours spread, and Koreans were massacred. People were anything but calm and orderly as Tokyo descended into chaos. The government needed to use martial law to restore order,” Dr Borland said.

“In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, concerns about children were paramount. Not only had they witnessed traumatic scenes of death and destruction, but two-thirds of Tokyo’s children also lost their homes and schools.

“However, just because children were the youngest and most vulnerable members of society did not mean that they were absent, voiceless, or invisible in the ruins of Tokyo. In fact, the opposite was true.”

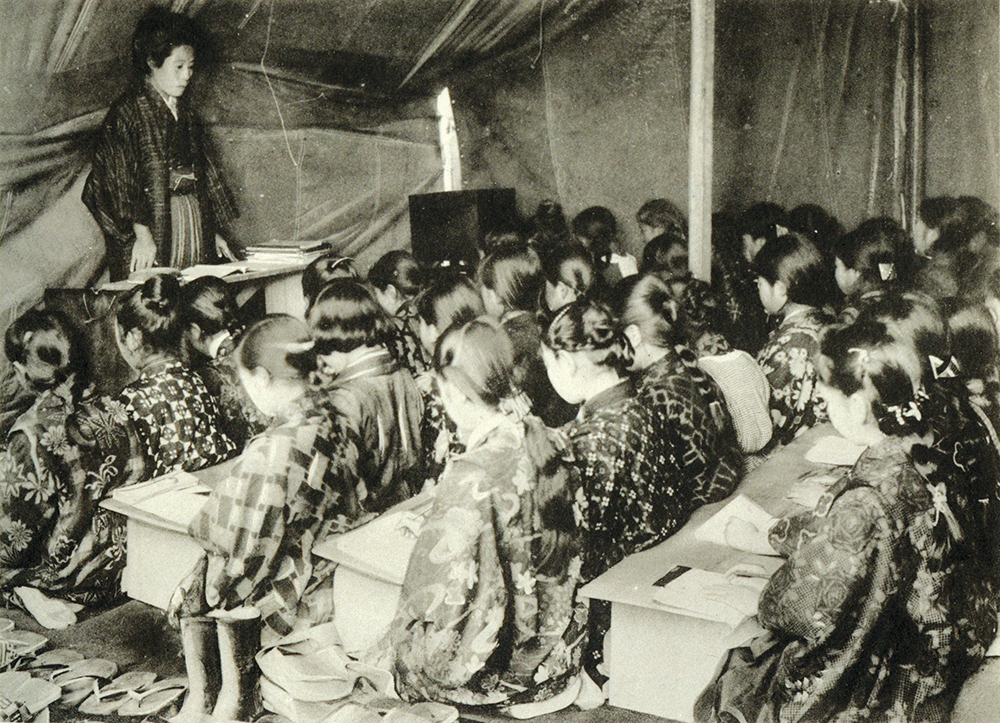

Children studying inside a tent classroom at Taimei Primary School, Tokyo, in 1923.

Stirring a response

One group – teachers – were determined to resume normal routine to help children’s recovery. A month after the quake, they resumed lessons amid the rubble and encouraged students to write about their experiences, which included everything from the fires to their pets or toys or friends they missed to their nightmares and noises that made them afraid.

The essays became part of a promotion by the government to commemorate the earthquake and rally people around the goal of reconstruction, and they were published in seven volumes. “Children were seen and portrayed as harbingers of hope, agents of recovery, symbols of resilience, and ambassadors of gratitude,” she said. Their plight also stirred emotional responses in adults, which the government used to its advantage during Tokyo’s reconstruction.

Dr Borland believes these essays and the focus on children – by teachers, physicians, seismologists, architects and politicians – were a first step towards Japan’s preparedness today.

All 117 wooden primary schools that had been destroyed by the earthquake and fires were rebuilt using reinforced concrete by 1930. Slowly, lessons were added to the national curriculum on what people should do and how they should act following a disaster. After a particularly destructive typhoon in 1959, the government fully strengthened disaster education in schools, and, tellingly, designated September 1 as National Disaster Prevention Day. Evacuation drills and disaster response training are now conducted on that date across the country.

“1923 was the origin of Japan today as a resilient nation,” Dr Borland said. “Since then, children, schools and education have been the primary tools through which officials have sought to build a disaster-prepared society and a disaster-resilient nation.”

HKU students paid a visit to the MORIUMIUS sustainable education centre in Miyagi to learn about the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Power of education

Dr Borland points out, however, that every natural disaster is different and disaster preparedness requires regular and ongoing revision, as the 2011 disaster reminds us. “The magnitude 9.0 earthquake was the fourth largest in history, yet many buildings survived the earthquake due to preparedness measures. Tragically, it was the tsunami that caused 93 per cent of the deaths,” she said.

Since 2017, Dr Borland has taken HKU students on a field trip to Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures to meet survivors and learn about their experiences. One person they meet is Fujimoto Nodoka, who was 11 at the time of the Tōhoku quake. “A key message Nodoka promotes is ‘tsunami tendenko’, which means to save your own life and evacuate to higher ground immediately after an earthquake, without searching for friends or relatives,” she said. “Nodoka now has a role in the community to share her story and inform people about what to do when an earthquake and tsunami strike.”

Dr Borland, reflecting on her own earthquake experience, hopes to achieve a similar goal. “There’s a lot of personal interest tied up in my story and I think that’s true of many earthquake survivors. We share a desire to teach people the lessons we learned so future generations can be better prepared.” That includes teaching her students at HKU. “The field trip inspired one of my students to move to Rikuzentakata and work in international relations. She now teaches the ‘tsunami tendenko’ message to people visiting the Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum. To me, that is testimony to the power of education.”

Earthquake Children: Building Resilience from the Ruins of Tokyo

Author: Janet Borland

Publisher: Harvard University Asia Center

Year of Publication: 2020

Since [1923], children, schools and education have been the primary tools through which officials have sought to build a disaster-prepared society and a disaster-resilient nation.

DR JANET BORLAND