November 2021 | Volume 23 No. 1

Museums of Remembrance and Forgetting

Museums tell a story as much by what they omit as what they contain.

The National Museum of American History includes displays of all aspects of the country’s past and welcomes about three million visitors a year. But two key groups – African Americans and Native Americans – have been highly marginalised.

The museum did not hold a comprehensive exhibition on slavery until 2012 and still does not address the ejection of Native Americans from their land, as Dr Tim Gruenewald, Programme Director of American Studies in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, argues in his new book, Curating America’s Painful Past: Memory, Museums, and the National Imagination.

This shortfall inspired the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016 and the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004, which were meant to spotlight their place in American history. However, he argues they also fall short because their remembering is largely disconnected from the present day.

While the new museums are state-of-the-art, have striking displays and celebrate the cultures they represent, they leave key figures untouched, particularly George Washington, and hold back from linking the wrongs of the past to those of the present day, such as racial inequity in the criminal justice system.

“I’m not against forgetting – to the contrary, I don’t think it is healthy to remember the trauma forever and ever. But you cannot suppress past collective violence before the problems have been dealt with. At the societal level, there is an obvious connection between the past and the present. But in the political realm, it is a different story because once you acknowledge the link, then you have to do something about it,” he said.

A display on American Indian Wars and forced relocation at the National Museum of American History.

Egregious omission

The African American museum does not pull punches about the past and draws on the example of the nearby United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to explicitly show the horrors of slavery and the pain of segregation. However, Dr Gruenewald said: “It finds a way to tell this story that does not disturb the secular religious space of US nationalism on the Mall.”

Washington was a major slaveholder, but this is not explored anywhere on the Mall, including the museum. “Washington is the most egregious omission in that context. We’re in Washington DC, the museum is next to the Washington monument, and this other version of American history leaves out the biggest name in town who also happens to have been one of the larger slaveholders of his time,” he said.

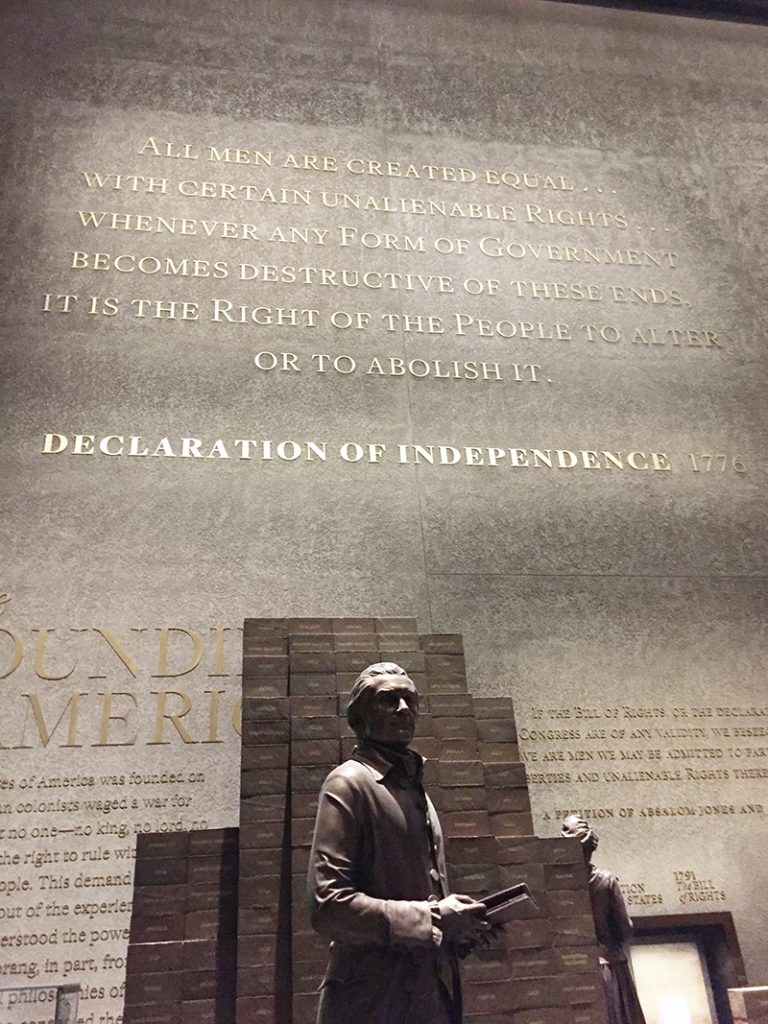

Thomas Jefferson’s slaveholding and racism are addressed, but his iconic phrase also receives the largest display – “All men are created equal”, from the Declaration of Independence, is visible over four storeys. The historical exhibition concludes with Barack Obama’s inauguration and Oprah Winfrey’s success as a female billionaire.

“The exhibition doesn’t hide anything about slavery, but what is the turning point in that story? It’s the Declaration of Independence,” which was written more than 85 years before the American Civil War that ended slavery.

“The dark past is embedded in a narrative structure that salvages the founding core ideologies of the national American imagination of equality, freedom and progress, and implies that it got better after the founding moment,” he said. “But that is not the whole story. Slavery expanded after independence and racial inequality persists until today, which I would argue has been marginalised in the museum.”

A sculpture of Thomas Jefferson at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Burden of remembering

Likewise, the Native American museum is soft on Washington. The museum had a somewhat controversial start because its displays were based around indigenous storytelling and mythology, not a traditional linear narrative of their history – partly due to their fraught relationship with museums which in the past have depicted Native American mannequins in dioramas “like stuffed animals,” he said.

But although recent displays have more directly highlighted the death, destruction and displacement they experienced under white men over 400 years, they also stop short at Washington.

“Washington is presented as the honest broker. The villain is Andrew Jackson [US president from 1829 to 1837] who expanded the policy of forced displacement. So again, they have done this in a way that leaves the larger national imagination intact. Washington is mostly a positive figure. We don’t have to change the discourse on the Mall,” he said.

Dr Gruenewald said he did not want to detract from the achievements of the two museums in celebrating their respective cultures. But as a scholar of public memory, it was important to consider how the past was remembered and connected to the problems of the present day.

“It should not be the burden of the African American and Native American museums to remember slavery and forced displacement – those communities know their past. It seems to me it should be the task of the country as a whole. And if any one group should do more then it’s the majority, the descendants of the perpetrators, who should have the burden to remember,” he said.

Curating America’s Painful Past: Memory, Museums, and the National Imagination

Author: Tim Gruenewald

Publisher: University Press of Kansas

Year of Publication: 2021

I’m not against forgetting – to the contrary, I don’t think it is healthy to remember the trauma forever and ever. But you cannot suppress past collective violence before the problems have been dealt with.

DR TIM GRUENEWALD