May 2022 | Volume 23 No. 2

Cover Story

Money, Markets and the Rise of Modern China

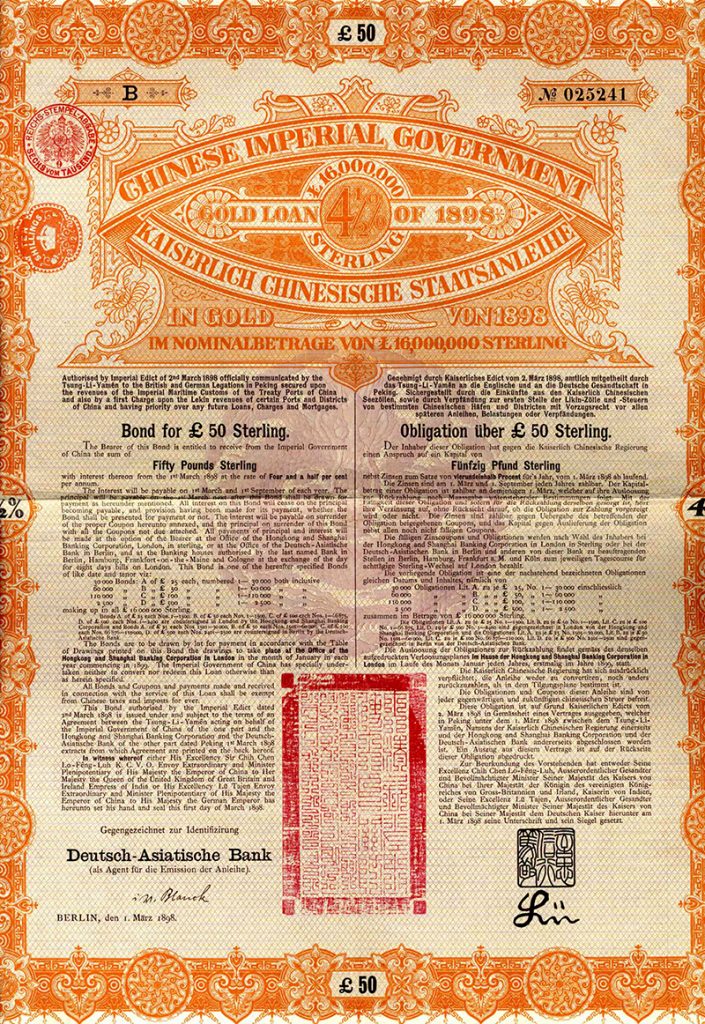

(Image courtesy of Ghassan Moazzin, private collection)

In the 18th century, the Qing dynasty was at its height: China was a global superpower and its coffers were full. By the end of the next century, all that had changed. While other major regions, in particular Europe and North America, were industrialising, China lagged well behind.

While there were many reasons for China’s weakness, recent research suggests that the lack of a unified currency and capital markets made it difficult for the country to emerge from the quagmire, according to economic historian Dr Ghassan Moazzin of the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences and the Department of History, who has written a book on foreign banking and international finance in China from 1870 to 1919 that is about to be published this summer.

“The Chinese government before the 19th century did not really get involved in the Chinese economy all that much. Then they realised that the country had fallen behind and they needed to come in and help the economy somehow,” he said. “If you want to do that, you want to have control of the currency. You also want to have your own capital markets at home where you can borrow money.” China had neither of these things.

On money, two kinds of currency circulated in the 19th century – copper coins issued by the government and used for everyday transactions, and silver, which was used for expensive purchases and, importantly, to pay taxes. The silver currency was imported mostly from Spanish America and each region within China had its own system of measuring and calculating the value of silver.

“The government did not really have any control over the supply and circulation of silver in the economy and this led to important problems,” Dr Moazzin said.

Bond for a Chinese government loan, 1898.

(Image courtesy of Deutsche Bank AG, Historical Institute)

Affecting state development

In the early 19th century, different factors led to the appreciation of silver, which in turn had a negative impact on the economy. The government made various attempts to deal with the problem, but it did not succeed until after 1927 when the Nationalists gained control.

“They managed to do a quite successful currency reform in 1935 but then the Sino- Japanese War came. It was only after 1949 that the Chinese government managed to properly reform the currency,” he said.

“When we think about how different generations of Chinese political leaders and reformers tried to build a Chinese nation, the monetary question and how to develop a unified Chinese currency system that the state has control over is not something that comes up much. But recent research by financial historians indicates that there is a thread that you can draw from the mid-19th century all the way to the mid-20th century.”

The lack of capital markets also affected state development. Unlike Western powers, China could not turn to markets at the outset of its industrial revolution to help fund railways, trading companies, large factories and other major ventures.

“For the Chinese state, it was just unthinkable that you would borrow money from your citizenry. If you had to do so, if your treasury was basically empty, it meant things were not going well,” Dr Moazzin said.

Cautious about foreign banks

To get funds for industrialisation projects, the government had to look abroad. Foreigners were happy to finance Chinese bonds because the return was better than many European government bonds. Other developing countries experienced the same phenomenon. “China could quite easily borrow money abroad, maybe a bit too easily, and later defaulted on a lot of that money,” he said.

Foreign banks, such as the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, helped connect the country to foreign markets and played an important role in the Chinese economy. They also issued their own banknotes, which further complicated the currency problem (in Hong Kong, some of these banks still issue currency).

While the government made some attempts to establish homegrown capital markets to borrow from Chinese investors, these did not really work until the 1920s – at which time it became more difficult to borrow from abroad. Since 1949, China has again gradually developed its own capital markets, but has at times also raised capital abroad.

A possible legacy of all this is that China remains cautious about foreign banks and has restricted their activities in the country. “We can connect this to the experience of foreign banks being so powerful in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in China. After the 1980s, the government was quite cautious to make sure that doesn’t happen again.”

Foreign Banks and Global Finance in Modern China: Banking on the Chinese Frontier, 1870–1919 is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

The government did not really have any control over the supply and circulation of silver in the economy and this led to important problems.

DR GHASSAN MOAZZIN